Workers’ Compensation: The Origin Story

May 31, 2024Author: Liz Maurer

A brief history of Workers’ Compensation

In the insurance industry, workers’ compensation claims can seem difficult to navigate. But the history and evolution of, what we call, workers’ compensation can offer a new perspective on how and why these systems became what they are today. The concept of compensation for bodily injury began thousands of years ago, shortly after the advent of written history itself.

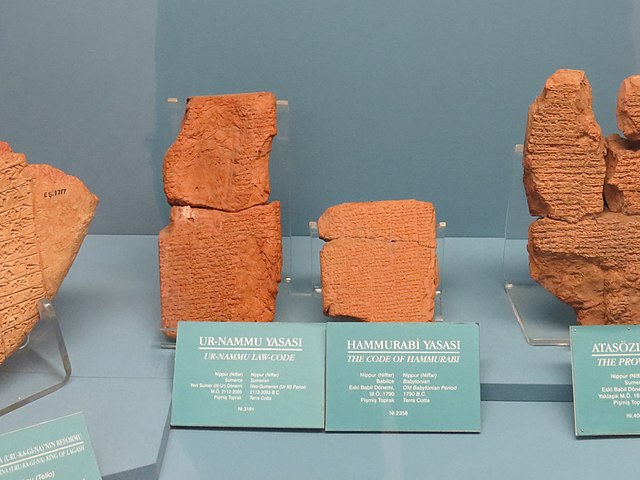

2100-2050 B.C.E. Ur Nammu

King Ur-Nammu, the ruler of the ancient Sumerian city of Ur, created the Code of Ur-Nammu, which was written on tablets and was comprised of 40 paragraphs containing both civil and criminal offenses, along with their punishments. Among other things like defining class rank and outlining the consequences of witchcraft, the Code of Ur-Nammu provided the first legal system in which monetary compensation was paid to injured victims. Much like modern day insurance, the amounts to be paid were based on the anatomic location of the injury as well as the severity.

This compensation system was also to be provided to laborers that were injured while performing their duties, making this the first documented instance of workers’ compensation in history. Heavy machinery and construction equipment didn’t exist in ancient times, so many workers’ injuries were caused directly by other people (and not always accidentally), so it was the offender’s personal responsibility to compensate the victim. The Code of Ur-Nammu became the basis for countless other legal codes and formed the foundation of legal systems still in place today.

The first copy of the Code of Ur-Nammu is currently on display at the Istanbul Archeological Museum.

1795-1750 B.C.E. Hammurabi

King Hammurabi of the Old Babylonian Empire brought us the Code of Hammurabi, famously known for its unforgiving tit-for-tat, or eye for an eye disbursement of justice. The focus was on physically punishing perpetrators rather than just compensating the victim. And while the punishments certainly seem harsh by modern standards, the Code of Hammurabi sought to protect workers from employers whose negligence caused them harm.

The Code of Hammurabi was one of the earliest examples of the concept of presumption of innocence and gave both the accused and the accuser the opportunity to provide evidence. If it could be proven that a worker was injured unintentionally, and not due to their employer’s neglect or carelessness, the employer was only on the hook for the victim’s medical costs, and they could keep all their limbs.

Workers’ Compensation laws continued to evolve in the coming years as ancient Greek, Roman, Arab and Chinese civilizations soon adopted their own sets of compensation schedules. However, all these very early schedules of compensatory rates were either overly specific or vague, leaving way too much room for interpretation in either direction.

The term “eye for an eye” comes from the Code of Hammurabi: “If a man has destroyed the eye of a man of the gentleman class, they shall destroy his eye.”

500s-1400s

These ancient compensation schedules were gradually replaced during the Middle Ages as feudalism became the primary structure of government. It was now up to feudal lords to make the determination about what, if any, injuries garnered compensation. Sometimes this worked in the victim’s favor, as it was an act of nobility and honor for a lord to care for an injured serf, but this was not always the case as not all feudal lords were so noble when nobody was watching.

1400s-1800s

The development of English common law in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance era gave rise to a new legal framework that persisted into the early Industrial Revolution across America and Europe. In response to the increasing number of free citizens entering the workforce doing more labor-intensive jobs, early English Common Law established three principals upon which it would be determined if an injury was compensable. But these principals were known to be so incredibly restrictive, that they became known as the “unholy trinity of defenses.”

- Contributory Negligence- if a worker was in anyway responsible for their injury, the employer would not be held liable, regardless of how hazardous the machinery or equipment may have been

- The “Fellow Servant” rule- employers were exempt from liability if a workers’ injuries arose out of the negligence of a co-worker

- The “Assumption of Risk”- employees are made aware of the potential hazards of any job once they sign their employment contracts, and they accept those risks. Because the risks were so high, these employment contracts became appropriately known as “Death Contracts”

Meanwhile in Prussia, Chancellor Otto Von Bismark established the Employers’ Liability Law of 1871.

The law provided social protection to workers who held high risk positions in factories, quarries, railroads, and mines. Several years later after the unification of Germany, Bismarck also created Workers’ Accident Insurance, the first modern system of workers’ compensation. These state-administered systems reserved large monetary benefits for job-related injuries, and covered both medical care and rehabilitation for injured workers.

Otto Von Bismarck was known for wearing a military uniform anytime he faced the public, even though he never actually served in the military.

The British eventually followed suit in 1893 with the proposal of the Workers Compensation Act, which would abolish the unholy trinity of defenses, including the issuance of “death contracts.” The Act held that an employee was entitled to compensation for any accident that was not their fault, even if there was no negligence on the part of the employer. Unlike the German model, the Act did not rely on the state to administer compensation, but it was instead up to organizations called “friendly societies,” which were mutual financial institutions similar to modern day insurance companies.

1900s- Present Day

The United States was slower to adopt the hot new trend of compensating workers for occupational injuries, giving rise to social movements like the “Muckrakers,” which was a group of authors who wrote about the struggles of working in the modern industrial society. The most famous among these was Upton Sinclair, who published The Jungle in 1906. His novel exposed the horrific conditions in Chicago slaughterhouses from an immigrant workers’ perspective in graphic detail and in no uncertain terms.

Upton Sinclair in 1900

In response to the growing unrest, Congress passed the Federal Employers’ Liability Act of 1908 under President Howard Taft which amended the unholy trinity of defenses to be less restrictive and more in favor of the worker. Keeping in mind this reform came at the federal level, it was still up to individual states to establish their own workers’ compensation guidelines.

In 1910, representatives of the industrial states assembled for a conference in Chicago with the goal of creating a unified set of guidelines for workers’ compensation law.

The first set of comprehensive workers’ compensation laws at the state level was passed in Wisconsin in 1911. Nine other states quickly passed similar legislation, followed by another 36 states before the end of the decade. Mississippi, the final state to pass workers’ compensation laws, finally did so in 1948.

In their original form, most state compensation acts made employer participation optional. But because employers who declined to participate were barred from using those common-law, unholy trinity defenses, the vast majority of employers opted in.

Today, after several thousand years of history in the making, our workers’ compensation systems are fully employer-funded through commercial insurance or through the creation of a self-insurance account, and nearly all states require employers to carry it. We have a much more sophisticated system of classification that has been tailored to fit each and every category of occupation, which allows insurers to provide infinitely more accurate compensatory rates to offer injured workers adequate compensation. The system, by nature, also carries incentives toward rehabilitating injured workers, which benefit both the employer and employee. And that’s why it’s so frustrating when we see people abusing and defrauding these systems that were created as a protection for them. The best thing we can do in our little piece of history is to make sure that these benefits are reserved for those who are genuinely entitled to them by proactively detecting, investigating, and reporting those questionable claims.

Sources:

- Insureon

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- Factinate

- History on the Net

- BBC

- World History Encyclopedia

- Lumen

- History.com

- Code of Ur-Nammu Image attribution: David Berkowitz from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Code of Hammurabi Image attribution: John Ross, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons